Going to visit my family down south is always a complicated thing for me. For one thing, it’s kind of going home, but not. We moved to that house just before I left for college, so I didn’t live there for long – maybe eight months. When I left, the water closed over my head quickly, my room taken over by my brother, my things sorted through and many of them tossed; my mother is not a sentimental keeper of things. And every year after I was gone, my father – a handy man with a hammer and saw – changed the house just a little – a wall gone here, a porch added there.

Dad, in his readin’ place.

There were plenty of things in the house that I remember, the ruby glass stemware, the little ivory pharaoh’s head from Egypt, the Stela Five stone that hangs over the fireplace, and the hundreds of books that filled the shelves wherever we went – things my parents gathered as we moved from LA to KC to NY, to TX. But I remember them in different houses, different contexts. (My sister remembers the places that were once home to us, but my brother doesn’t.) So when I see these things now, they come with a confusion of images and feelings. And, of course, the biggest difference in home is that my mother is no longer living there.

Things they picked up on all kinds of trips, the corn cob girl from Arkansas, the other things – other places. My dad built the little yard she stands in; I’m certain of that. We do Autumn well in our little fam.

Things they picked up on all kinds of trips, the corn cob girl from Arkansas, the other things – other places. My dad built the little yard she stands in; I’m certain of that. We do Autumn well in our little fam.

The little town of Arlington is now a teeming metropolis; the little wooded country roads I “knew” are now four and six lane highways and there are strip malls and stadiums and the traffic is incredible. There is little in that place that I actually remember. Only our house. Our little street. And a precious few people outside of my father and my sister and her family.

I have shot very few images in the last month. Too engaged in motion to remember to freeze things. Everything I shot in Texas I did with my iPhone, thinking it would do very well. It didn’t. Holy cats, it didn’t. And most of the stuff was low light. Blur, grain. These are the worst shots ever. But I still love them. Dad had these three fabric pumpkins in his living room. My sister made them. He told me she’d made mounds of these things, but i didn’t catch the vision till I went to her house.

But my sister and I have fun there. She drags me around to interesting places – I say “drags” because I feel like dead weight, not having any idea where I am, making no suggestions cause I don’t have any. We laugh a lot. And I run errands with Dad, and we eat dinner together and are happy as clams settling down to an evening movie, then early to bed.

In every corner – yes – glorious mounds. Handmade glorious pumpkins that I coveted. These fabric choices are SO GREAT.

It’s seeing my mom that takes the experience from Happy Visit to Twilight Zone. She lives with some twelve other people in a place that is much nicer than my house – all crown moldings and classy paint colors. The lighting is cheerful, and there’s always music, always someone cleaning and attending. The building is all bedrooms around the outside, circling the two living room areas where the people congregate, most of them in wheelchairs, many of them unable to walk or make sense. It smells nice.

Dad’s kitchen.

My father goes every day or every other day, sometimes twice. He finds my mom in her rolling lounge chair—taller seeming than I ever knew her, perhaps because she weighs next to nothing. Boy haired. She puts a lot of energy into the conversations that never stop. But it’s almost impossible to make out what she might be saying. He walks her around the building – the hall makes a gentle oval path. And as they walk, he repeats a mantra – “You are – “ he starts, giving her full name, reminding her of his, and of her children’s names. Giving her a fixed moment of identity – if she hears him. She is, as she has always been, willing to laugh when she knows he is being funny. Willing to respond, whether it makes sense or not.

I want twenty of these. Kev is so danged clever.

Even BYU ones.

The question we share and try not to say out loud has to do with how much she actually understands. Whether she is locked in a dream, or perhaps lives with one foot in the next life – or whether she is trapped in a body that no longer responds to her aware and intelligent still-self.

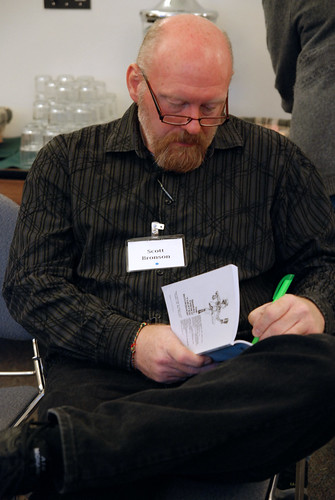

The first time we visited, Dad and I this time, I walked around with them. Each room has a little framed shadow box hanging beside the door – maybe two and a half fee by a foot and a half. People put things there – signs with the patient’s name on them, sometimes family pictures, a wedding picture maybe, or even the person as a child. And then other things, mementoes. Things attesting to the fact that this person was once real – mothers, teachers, professional people. We passed one that said, “Dr. Andrea Something.” On the faculty of a prominent law school. A judge. Now, nothing more than a person unplugged, sleeping in a borrowed bedroom with a few of the million things that once made up her home, challenged at the impossible task of putting three cogent words together.

I had to talk about that. How chilled I was. People’s lived distilled into one small picture frame. Their world a wheelchair and a dinner schedule. After a while, I started to talk about how Mom had, after taking care of her own mother who was in this same state, been terrified of finding herself in the same place. And told Dad about a dream I’d had, a reassuring one, suggesting that wherever you are, you an always try to help somebody else. You can do the best you can. And then I looked down at mom and said some stupid thing like, “. . . which I’m betting Mom did when she got here.”

She had been talking. But now I think of it, she’d been quiet as I’d said these things. She started talking again, after I said that thing. And these were actual words. I heard them. Garbled, but I could hear the solid shape of them. She said, “Yes. Yes. When you get here you don’t know where you are. You don’t know what you’re doing.” My heart about stopped. Then she said, “And nothing you have means anything.” After that, the words just became syllables and consonants again.

The next time we went, I was expectant. But in all the muttering my mother did, not one word took recognizable form. She did look me in the face, twice, but as though I were some disturbing night vision. The whole thing still haunts me.

When I visit, my sister lines up projects for us to do in Dad’s house. He doesn’t want stuff around. No boxes of pictures. No shelves with things unused on them. We cleaned out the garden shed. I didn’t know that mom had given gardening and lawn care a shot, but there was this shed, full of fertilizers and bug spray. Something in one of the bottles had eaten a hole right through the metal shelf it had sat on.

Her Autumn tree. The living room is so inviting. I wish my images were better.

And then there where some cabinets in the TV room. We’d already been through most of them. But these were full of mom’s books. Some, I knew well. I remember seeing Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring on the shelf over the kitchen table all through junior high and high school when we lived in New York. There were books about nutrition and healthy cooking, food storage, bread making. She’d saved pages out of magazines and pamphlets, books about crocheting and gardening. Just all this domestic stuff. But mostly about health. She was a chemist, and keeping us healthy was her passion. That, and avoiding cancer.

I don’t know how to explain this. Sometimes, things people own become so synonymous with who they are in your life that when you see the things, you feel the people. Those books were the scent of mother, the feel of her. And we took them off the shelves, the big ones one at a time, the smaller ones in clumps and piles. And collections of recipes, written in her own hand, filed in wooden boxes. More potent mementos than pictures or a lock of hair. Some we kept. But we each have our own lives, our own burgeoning shelves. I have my own collection of pages pulled out of magazines – things I mean to take a good look at some day. Ideas worth saving.

This one was store bought, but she put the twine between the sections and gave it a leather stem.

And we threw the rest away. No longer worth saving. Too late for Mom to get that good look at them. I realized that she’d actually accomplished what she meant to – we were all healthy. Her body is impressively healthy. She never got cancer. She lived a long and solid and happy life. So really, she won. In the end, she won. Except for this. This brain thing. I felt like we were closing up her life in those boxes. And we took them to Half Price Books, about six heavy boxes crammed with books, all old science now, but such an intact collection of thought.

They gave us six bucks for the whole thing.

And all of this sounds sad. But it wasn’t. Because Kev and I had had a great time being together. Some things we’d gotten a good laugh about. Some things were memories. It had been a warm and companionable and strange afternoon. Our mother’s books.

I came home – flying American. They got me to the airport in perfect time. But the west had been stormy. We waited for the crew. Forty minutes later, the crew finally got there and ran safety checks. I had prayed thus: please do not let this airplane take off with us in it if anything’s going to go wrong. “We found a couple of problems,” they told us. Fifteen minutes later, they said, “We are taking this airplane out of service.” So they sent us to another terminal to another plane that had to be warmed up, gone over, stocked with food, filled with luggage. I wasn’t put out. That’s what you get for praying.

Three absolutely adorable LDS missionaries from Bristol, UK, on their way to Provo, Utah. After that, one stays in Utah, one is off to Ukraine and the other to the Philippines. If we had to wait forever, at least we were in good company.

And when I finally got home—three hours late—I went to bed and slept until I woke up. Then I rolled up my sleeves and started taking the house apart, piece by piece, dusting and oiling wood, and generally setting the stage for the holidays. I couldn’t sit down and write anything. Just comments here and there on beloved blogs. I just worked.

And now, I sit here in the gloaming – we have finished Thanksgiving dinner, cleaned up the dishes several times. I have sworn off dressing, gravy and pie. My Christmas lights are up and on. The wind is roaring through the yard, stripping already beaten trees of their last leaves. And I am waiting for the gift-buying frenzy to settle so I can buy a few more strings of lights to replace the ones on the tree (our beautiful fake tree – lit in eight hours four years ago) that have inexplicably died over the summer.

This is not a story with any respectable narrative form.

I have been with my children around the table, eaten well. And talked on the phone with the ones who were out of state, out of sight, never out of mind. For the moment, all is well – and our lives are flowing like a river, peaceful, heavily forward, inexorably forward, all of us together bobbing along on the service, all tangled up in each other’s lines and rigging. We sing sailing songs and do a lot of talking and laughing and sometimes we throw stuff at each other.

I don’t know how I’ll end up. And at the moment, I don’t care. For now, it’s all books and creation and love and worrying about the stupidity of politics and trying to remember to eat when there are so many things to do that are far more interesting and compelling than eating. And as long as I can make choices, I will. And save what I can so the kids aren’t stuck paying for me.

You never think about these things when you’re young.

And yet – I’m pretty sure I’m going to be young forever. One way or another.

So, if you had to sum up your entire life’s significance in a shadowbox, what things would you put in there? Your name? Your tools? Pictures of your children? It’s something to think about.